Early Immigration and Its Origins

In 1863, at the tender age of 12, Gojong ascended the throne as the 26th king of Joseon. His father, Heungseon Daewongun, took up the regency and implemented an isolationist policy. In 1866, Daewongun ordered the execution of nine French missionaries, including Catholics Hong Bong-ju and Nam Jong-sam, and issued a decree that led to the massacre of many Catholic believers across the eight provinces.

In August of the same year, the American merchant ship General Sherman sailed up the Taedong River carrying steel and glass products and proposed trade relations, but the feudal government of Joseon refused. When Americans attempted to land in Pyongyang using a smaller boat, a clash ensued resulting in the death of Pyongyang officials.

After a minor three-day conflict, the General Sherman was eventually set ablaze and sank. In response, in 1871, the United States dispatched five warships to investigate the incident. The US forces attempted to occupy Ganghwa Island but were forcefully repelled by the steadfast Korean defense, marking the event known as the “Shinmiyangyo.” Similarly, Japan caused the Unyang-ship incident in Ganghwa and coercively forced Korea into signing the “Ganghwa Treaty” on February 26, 1876.

As Korea gradually opened its doors, the major powers competed to establish diplomatic relations. On May 22, 1882, in Jemulpo, with the help of Li Hongzhang of China, Joseon’s plenipotentiary ministers Shin Heon and Kim Hong-jip signed the Korea-US Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the American envoy, Navy Admiral Shufeldt, aboard the USS Swatara. This treaty was the first to be concluded with a Western nation, followed by similar treaties with Britain and Germany in June at the same location, making Incheon a leading port of entry to Joseon. Following the treaty, in May 1883, the US dispatched Lucius Foote as the first American minister to Korea. In commemoration, King Gojong sent the Bae-bing-sa Delegation to the United States on July 16, 1883, led by Min Yeong-ik, and including Hong Yeong-sik, Seo Gwang-beom, Yu Gil-jun, and Byeon Su.

Accompanied by their American advisor, Frederick, the delegation from Joseon arrived in San Francisco on September 2, making this the first such visit in Korean history. They stayed at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco for a week before traveling by train to Washington, D.C.

Throughout their journey, they carried and displayed the Korean flag at various events and accommodations to assert Korea’s sovereignty and independence through what can be described as diplomatic self-assertion. During their time in the United States, they developed a favorable impression of the country and realized the necessity for Korea to adopt modern institutions and cultural practices. Yu Gil-jun did not return with them but instead stayed to study in the United States as the first Korean government-sponsored student. After expanding his experiences in Europe, he returned home and wrote “Seo Yu Gwanmun,” introducing the Western world to Korea for the first time. His book made many Korean scholars admire the Western world, and those who were part of the delegation advocated for gradual reforms in Korea.

However, due to differences of opinion with those eager to implement reform policies, the Gapsin Coup occurred in October 1884. Following the failure of the reformists, figures like Seo Gwang-beom, Seo Jae-pil, and Park Yeong-hyo became exiles and fled to San Francisco in 1885.

The key figures of the Gapsin Coup of 1884 were:

Park Young-hyo

Seo Kwang-beom

Seo Jae-pil

Kim Ok-kyun:

In 1887, as part of King Gojong’s efforts to assert autonomy in foreign relations and promote enlightenment policies, the first minister plenipotentiary to the United States, including Park Jeong-yang, Lee Wan-yong, Lee Ha-young, and Lee Sang-jae, was dispatched. This move also facilitated the invitation of diplomatic and military advisors who supported the enlightenment policies. However, when Park Jeong-yang took office as the minister in January 1888, China pressured him under the pretense that Korea was not under its control, forcing him to return. Upon his return, he wrote “Misok Sipryu,” detailing American systems and customs, which influenced the Korean government and King Gojong to have a favorable view of relations with the United States.

By 1894, the Donghak Peasant Revolution and the assassination of Empress Myeongseong in 1895 had unsettled society and disturbed public sentiment. The next notable group of Koreans to travel to the United States were a few ginseng merchants from Uiju who went after 1898. They were very few in number and often passed themselves off as Chinese, thus being treated as such.

Before Hawaii became a U.S. territory, on January 15, 1900, Yang Baek-in (31) and Kim Yi-yu (34) were recorded by the U.S. Immigration Bureau as the first Korean entrants. At the time, Yang had $180 and Kim had $400, a substantial amount likely due to their involvement in the ginseng trade, which was sold at high prices to Chinese buyers. This period followed the 1849 San Francisco Gold Rush boom, where Chinese immigrants, who were involved in mining for residual gold in abandoned mines, highly favored Korean ginseng.

After Hawaii was fully annexed as a U.S. territory on June 14, 1900, the actual first civilian Korean to enter the United States was Yoo Du-pyo, who arrived on January 9, 1901. Koreans were allowed to immigrate to the U.S. based on Article 6 of the Korea-U.S. Treaty, which stated that Koreans could “travel and reside anywhere in the United States, purchase and sell land and buildings, construct buildings, and engage in any business according to the law.” Prior to the formal opening of immigration to Hawaii, those who came to the U.S. included officials, political exiles, students, and merchants, with the total number estimated to be around 30 individuals.

In the Korean-American community, three influential figures were Ahn Chang-ho, Syngman Rhee, and Park Yong-man. Ahn Chang-ho entered the U.S. in 1902, Syngman Rhee in 1904, and Park Yong-man in 1905, all for educational purposes. Other immigration leaders like Yun Chi-ho, Kim Kyu-sik, and Lee Kang also crossed over to the U.S. around this time.

Following the Eulsa Treaty on November 17, 1905, which transferred Korea’s diplomatic rights to Japan, the U.S. government closed its consulate in Seoul on November 30, and the Korean consulate in Washington, D.C. was also closed on December 16.

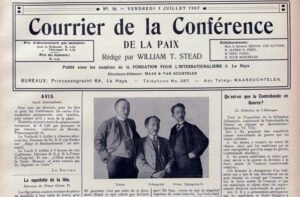

Meanwhile, after the Eulsa Treaty, King Gojong sent three secret emissaries – Yi Jun, Yi Sang-seol, and Yi Wi-jong – to the Second International Peace Conference in The Hague, Netherlands, in 1907, in an effort to inform the world about Korea’s plight.

The participants at the Hague International Peace Conference were Yi Jun, Yi Sang-seol, and Yi Wi-jong.

Leave a Reply