Just as the saying goes that adversity breeds great leaders, the early Korean community went through numerous hardships and produced many outstanding leaders. These individuals, worried about the bleak future of their homeland, spearheaded the independence movement. Simultaneously, they engaged in enlightenment activities for immigrants, urging Koreans to argue for and improve their living conditions with utmost effort.

Seo Jae-pil was born in Boseong, South Jeolla Province, and moved to Seoul at the age of seven. At fourteen, he excelled academically, achieving the highest honors in his exams. He was introduced to enlightenment ideas through Kim Ok-gyun, which led him to study at a military academy in Japan. Later, he and Kim Ok-gyun attempted to establish a military academy in Korea but were thwarted by conservative factions.

Along with Kim Ok-gyun and Park Yeong-hyo, in 1884, Seo Jae-pil was involved in the Gapsin Coup, an uprising where the enlightenment faction sought to overthrow the pro-Chinese conservative government and assert equal rights for the people. He held positions in the new government as the Deputy Minister of Military Affairs and as a government administrator. However, when the coup was suppressed by Chinese military intervention after just three days, Seo fled to Japan. There, he received tragic news: his parents and wife had committed suicide due to his actions, his brother had been executed, and his only child, aged three, had died of starvation.

When the Japanese government began persecuting asylum seekers, Seo Jae-pil, along with Park Yeong-hyo and Seo Gwang-beom, sought refuge in San Francisco in April 1884.

“COREAN REFUGEES. Exiles from the Hermit Nation. THE WAIFS OF A REBELLION. San Francisco as the Asylum for Three Leaders of the Progressionists.

On June 19, 1885, the San Francisco Chronicle published an article about the asylum of these individuals stating: “There are living in strict seclusion in this city three Coreans of high rank, who have within the past year passed through an exciting period, which, in all probability will leave an impress on their lives that will never be effaced. Their names are Pak Yong Hio, Soh Kwang or Jo Kohan Pom, and Soh or Jo Jai Phil.” One of them worked for two dollars a day, walking ten miles to distribute furniture store flyers, struggling with painful and cracked feet that made it hard to sleep. The work was so grueling and his situation so dire that he even thought of throwing himself into the Pacific Ocean. However, this newspaper article connected him to Americans who helped him.

Seo Jae-pil encountered Christianity while attending a Bible study class at the Mason Street Presbyterian Church in San Francisco, where he met Hollenbeck, who greatly influenced his life. Hollenbeck wanted to make him a missionary and enrolled him in a high school in Pennsylvania. Extremely intelligent, he skipped a year and won second place and a ten-dollar prize in a school competition with a tribute to President Garfield. He graduated with honors in just three years and during this time, he changed his name to Philip Jaisohn and became the first Korean to acquire American citizenship.

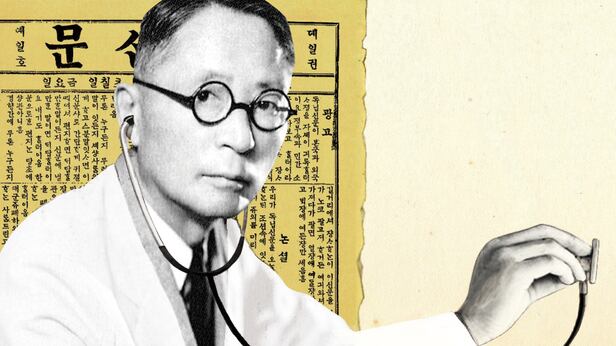

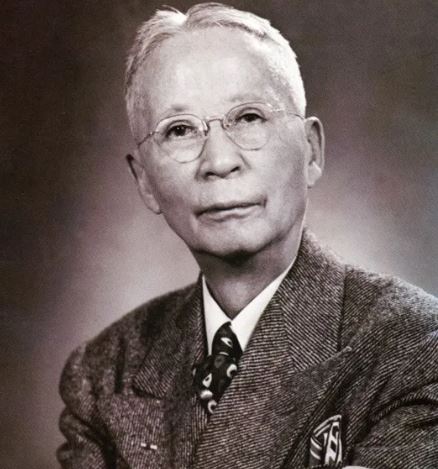

After struggling through his studies, he graduated from Columbian College (now George Washington University) in 1892 and went on to become the first Korean to earn a medical degree. In 1894, he married an American woman, Muriel Armstrong. Following the amnesty of the Gapsin Coup leaders and the establishment of a reformist government, he returned to Korea in 1895 to contribute to his country’s enlightenment. On April 7, 1896, he founded Korea’s first civilian newspaper, The Independent, using simple Korean language and spacing to make it accessible to the illiterate populace. On July 2, 1896, he founded the Independence Club and organized the People’s Joint Association. He also led Korea’s first modern civic rally, the People’s Joint Meeting, in Seoul on March 10, 1898, denouncing Russia’s aggressive policies. However, in May 1898, the conservative government and foreign powers involved expelled him to the United States.

After the March 1st Movement of 1919, Seo closed his medical practice and plunged into the independence movement. On March 15, 1919, at the All-Korean Residents Meeting in America, he was appointed diplomatic advisor and established a Department of Diplomacy in Philadelphia, engaging in propaganda activities for Korea’s independence. In April 1919, he held the Korean Freedom Conference in Philadelphia, which adopted a resolution asking the League of Nations and the United States to recognize the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. He led a procession to the Independence Hall on the third day of a freedom speaking event, with 150 Koreans marching under the pouring rain, carrying the Korean flag through the streets of Philadelphia.

Later, as chairman of the Korean Commission in Washington, he formed the League of Friends of Korea in May 1919, which expanded to include 10,000 members and 17 chapters across the United States, actively campaigning for Korea’s independence. In August 1919, he launched the Korea Review, an English monthly, as editor-in-chief, promoting the justification for Korean independence worldwide. In November 1921, he submitted a request for Korean independence at the World Disarmament Conference and met with President Harding in January 1922 to seek support.

On July 1, 1925, he attended the Pan-Pacific Conference in Honolulu, Hawaii, as a representative of Korea, condemning Japan’s aggression and advocating for Korean independence. His impressive speech and activities at this conference led to his election as deputy chairman, and he used this position to appeal to representatives of various countries to support Korean independence.

After the March 1st Movement, he sold his hospital and stationery store, raising $76,000, which he donated entirely to the independence movement. Facing bankruptcy, he borrowed $2,000 in 1926 and returned to graduate school to further his medical research, leaving significant contributions.

During World War II, he served for four years as a conscripted medical officer and received a commendation from the U.S. Congress. After Korea was liberated on August 15, 1945, he briefly returned to Korea and was appointed as a senior advisor to the U.S. military government and as a special legislative officer. On September 25, 1948, when a movement emerged to nominate Seo Jae-pil as president, opposition from Syngman Rhee’s faction began. As the political scene in Korea grew turbulent, he resigned from all his positions and returned to the United States. On his way back to his home in Philadelphia, he stopped in San Francisco and Los Angeles to relay news of the homeland to Dosan Ahn Chang-ho’s eldest son, Philip Ahn, and officials of the Korean National Association.

Upon returning to Philadelphia, he opened a medical practice in a small town nearby and cared for patients for three hours each weekday. When the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, he deeply lamented the misfortune of his homeland. He passed away on January 5, 1951, at the age of 86, in Philadelphia.

In 1977, the government posthumously awarded him the Republic of Korea Medal of the Order of National Foundation.

Related Readings

Leave a Reply