1 The History of Independence Movements in San Francisco

On March 23, 1908, at the San Francisco Ferry Terminal, the incident where Jang In-hwan and Jeon Myung-woon assassinated Stevens became a pivotal moment, showcasing the Korean people’s spirit of freedom and anti-Japanese sentiment to the world. For the Korean community in America, it marked a new beginning for the independence movement, seizing the opportunity to alert mainstream American society and the world to Japan’s invasion of Korea. The independence movement, which had been somewhat scattered in America at the time, underwent a significant transformation due to this incident. The patriotic actions of the two doctors, risking their lives, led to the creation of a unified anti-Japanese independence organization, the “Kookminhoe” (National Association), on February 1, 1909, from scattered groups across America. Though Jang In-hwan and Jeon Myung-woon were the defendants in the incident, in a broader sense, they had put Japan’s imperialist invaders on trial in the court of world public opinion.

This incident also had a profound impact on the consciousness of Korean individuals, galvanizing them to unite all efforts towards the movement for Korea’s independence. It sparked concrete strategies for effectively regaining national sovereignty, both domestically and internationally. This event, only illuminated a century later, remains a crucial incident with many aspects yet to be studied. The patriotic struggle of the two men, who risked their lives to save their country, initiated by three gunshots in San Francisco, was a significant historical moment that reinforced national consciousness, established nationalist ideas, and highlighted the movement for the recovery of sovereignty in Korean history and the history of Korean immigration to America.

The Origin of the Incident

Stevens, an American who worked as a counselor at the U.S. Embassy in Japan, was dispatched to Korea as an advisor to Emperor Gojong in August 1904, as Japan prepared to annex Korea. He was a pro-Japanese figure, closely associated with several high-ranking Japanese officials, including Itō Hirobumi. The Japanese government utilized Stevens to justify their invasion and garner the understanding of the U.S. government and public opinion. Stevens announced his visit to the United States under the pretext of a vacation. There were rumors that he continued his pro-Japanese activities while receiving substantial bribes from the Japanese residency-general. Koreans perceived him as “more Japanese than the Japanese” and “more loyal than Japanese officials.” In contrast, foreigners like Hulbert, Bethel, and McCune, who keenly understood international politics and Japan’s ambitions, criticized Japan’s atrocities in Korea through books, magazines, and newspaper articles.

Arriving in San Francisco on March 20, 1908, Stevens held a press conference with the San Francisco Chronicle, where he made reckless remarks such as, “Korea is actually benefiting under Japanese rule, and ultimately, the U.S. will benefit as well.” He continued, “First, since Japan has protected Korea, many beneficial things have happened in Korea, and relations between the two countries have become closer. Second, Koreans are illiterate and uncivilized, incapable of self-governance, and Japan ruling Koreans is similar to the U.S. governing Filipinos. Third, if Korea were not under Japanese rule, it would have fallen under Russian control by now. Those who oppose Japan are only those who could not participate in the new government, but farmers and ordinary people welcome the Japanese as they no longer suffer the abuses of the previous Korean government. Fourth, Japan is working hard for the Koreans, who are happy and enjoying better lives than before.”

On the same day that Stevens arrived, another ship carried a letter from anti-Japanese activists in Korea, calling for Korean compatriots in San Francisco to rise against Stevens, who had conducted highly pro-Japanese diplomatic activities in Korea. At the time, the U.S. was experiencing a movement to exclude Japanese laborers, with a related bill proposed to Congress, which was set to be discussed in December. Japan aimed to use Stevens’ visit to prevent the passage of this bill by having him interact with members of Congress and influential figures.

Reactions from the Korean Community

When the contents of Stevens’ press conference were prominently reported in the Chronicle, the Korean newspaper Gukminbo published the article on its Saturday edition. The Koreans who read it were outraged. The next day, Koreans gathered at the Korean Methodist Church in San Francisco, fervently condemning Stevens and calling for action. On the evening of March 22, the Gongnip Association and the Daedong Bogukhoe jointly held an emergency general meeting.

According to the testimony of Seon Woo-tan, about 50 people attended the meeting held at the Gongnip Association hall. Records indicate there were about 150 Koreans in San Francisco at the time. Reverend Yang Joo-sam, who presided over the meeting, suggested discussing “how to deal with Stevens, who insulted our sovereignty and nation.” Young student Jeon Myung-woon passionately declared, “It’s an outrage. This misfortune happens because our country is weak. We must act. We should kill him.” Other attendees also condemned Stevens. They argued that if the Korean community did nothing in response to Stevens’ remarks, the American public would look down on them, and specific measures needed to be taken.

After the discussion, four representatives were elected: Lee Hak-hyun and Moon Yang-mok for the Daedong Bogukhoe, and Choi Yoo-seop and Jeong Jae-gwan for the Gongnip Association. These representatives immediately went to the Fairmont Hotel, where Stevens was staying. Stevens, expecting Japanese friends, was startled to see Korean representatives and turned pale. The representatives interrogated him, asking if he acknowledged the statements in the newspaper and demanded corrections and an apology. Stevens arrogantly repeated his pro-Japanese rhetoric, praising Ito Hirobumi and Japan’s governance of Korea, and refused to retract his statements.

Jeong Jae-gwan and Choi Yoo-seop reacted violently, with Jeong hitting Stevens, leading to a physical altercation. The hotel staff and guests intervened, and the Korean representatives boldly explained Stevens’ actions and Japan’s atrocities. Despite the commotion, Stevens declined to press charges against the Koreans, possibly to avoid further diplomatic issues. The police, influenced by Stevens’ attitude, merely asked the Koreans to leave.

The Chronicle reporter who learned of the incident asked the representatives why they assaulted Stevens. Lee Hak-hyun responded, “It was a matter of liberty or death for us. We will take responsibility for our actions and are not afraid of being arrested. We will fight for freedom.” Moon Yang-mok added, “We are patriots of Korea. Look at your history. American patriots opposed Britain. Korean patriots oppose Japanese imperialism. Any state or individual supporting Japanese oppression of Koreans is our enemy. Stevens is our enemy. Just as you love America, we love Korea.”

After reporting the continued insults from Stevens and the hotel incident to the waiting Koreans, they discussed further actions. At this point, Jeon Myung-woon volunteered, “I will take care of it,” and Jang In-hwan, who had been quietly standing by, declared, “If someone gives me a gun, I will shoot him.” Plans were made overnight, and they learned of Stevens’ revised schedule due to his heightened sense of danger. He planned to leave for the East Coast via Oakland by taking a ferry from San Francisco Ferry Terminal on the morning of March 23.

The Assassination

Feeling threatened after being assaulted by Koreans, Stevens not only advanced his schedule but also handed over two letters to the Japanese Consul General, asking them to be delivered to Ito Hirobumi and Japan’s Foreign Minister if he died. The letters included instructions for compensation to his two sisters and statements about his work for Japan over 22 years.

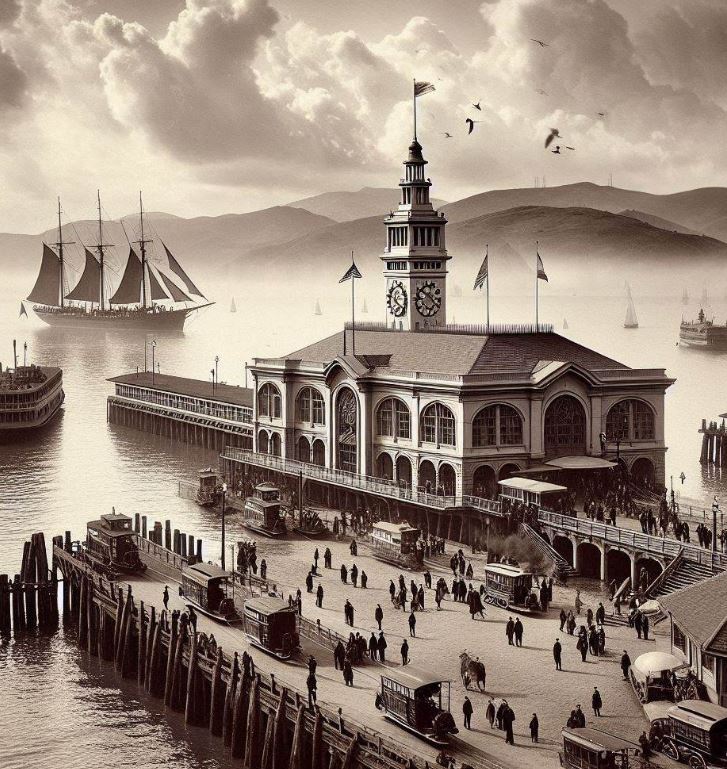

On March 23, 1908, at 9:10 AM, as Stevens arrived at the San Francisco Ferry Terminal and stepped out of the car, he was greeted by Japanese Consul General Shoji Koike. Jeon Myung-woon aimed his gun at Stevens but the gun misfired. He then tried to hit Stevens with the gun, leading to a scuffle. At that moment, Jang In-hwan emerged and fired three shots at Stevens, the first hitting Jeon Myung-woon’s shoulder due to the struggle, and the subsequent two hitting Stevens in the back and waist, causing him to collapse.

The scene turned chaotic, and the police immediately arrested Jang In-hwan. Both Jeon Myung-woon and Stevens received emergency treatment at a nearby hospital before being transferred to St. Francis Hospital.

Leave a Reply