Americans originally believed in the doctrine of predestination as taught by Christianity. This doctrine instilled in them a sense of being the chosen people, believing they were specially selected by God from birth. Consequently, they harbored feelings of superiority and looked down on people of different skin colors. This sense of chosenness, coupled with language barriers and cultural differences, led to severe racial discrimination and suffering for early Korean immigrants. At that time, racial discrimination was not only legal but also considered a normal part of society. There were no appropriate methods or places to lodge complaints, no matter how unjust the treatment was. Unlike today, the notion of the United States as a nation of immigrants was not recognized, forcing those who left their homeland to endure their circumstances.

Not only Koreans but all Asians were targets of racial discrimination. After the Pearl Harbor incident, Koreans, who could not be distinguished from Japanese, faced even greater disadvantages.

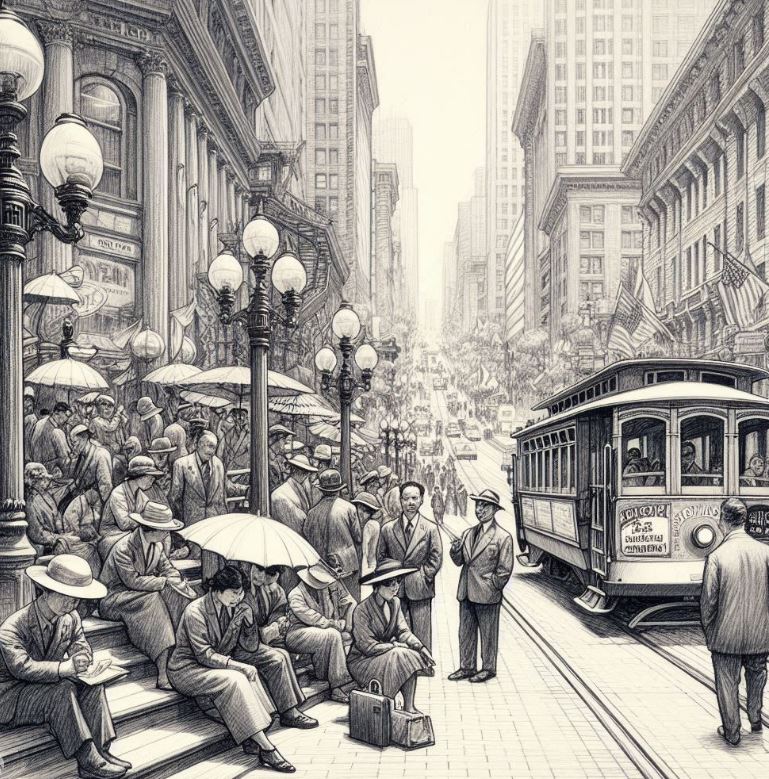

White Americans viewed “yellow people from the East” as mysterious, immoral, and fanatical. This belief led to the emergence of the so-called “Yellow Peril” theory, intensifying the hostility towards Asians. The fear of Asians persisted, reminiscent of the era when Genghis Khan from the East ruthlessly conquered the world. People hostile to Asians believed they were dangerous. Furthermore, Asians were seen as taking away jobs from whites by working for lower wages.

Between 1911 and 1916, Asians were barred from entering hotels during travel, could not buy food from restaurants even if hungry, and were not allowed haircuts at barbershops if they had long hair. Despite these humiliations, early immigrants endured everything with the hope of returning to a liberated homeland someday. Intellectuals and political exiles found it particularly difficult to bear the severe humiliation and racial discrimination. The only jobs available to them were washing dishes or cleaning other people’s homes.

Until the Civil Rights Act was passed in the 1960s, signs in American restaurants often stated, “We reserve the right to choose our customers.” This was essentially a declaration that they would not serve Asians or Blacks.

First-generation immigrants struggled with the language and had already made a solemn decision to leave their homeland, often accepting discrimination as their fate.

However, second-generation immigrants born in the United States found it more challenging when they were bullied and ridiculed by their peers. They often fought back against the teasing children and blamed their parents at home.

Some second-generation immigrants viewed Korea as a primitive country and felt ashamed of their identity. This sentiment was partly influenced by missionaries who described Korea as a primitive country in dire need of missionary work during their reports and fundraising activities.

Anti-Asian Sentiments in the United States

- October 11, 1906: The San Francisco school district ruled that Japanese and Koreans born in America could not attend schools with white children. Instead, they were directed to attend schools for Chinese south of Clay Street. At the time, there were about 110,000 Japanese, 45,000 Chinese, and 1,000 Koreans in the area.

- February 17, 1908: California Congressman Hayes introduced a bill with four provisions to exclude Asians, including Japanese, Koreans, and Indians, from the United States.

- 1908: In San Francisco and Oakland, groups formed to prevent Japanese from operating laundries and working as cooks and waiters, supported by labor unions.

- February 28, 1909: Various laundry businesses in San Francisco united to exclude Japanese laundries, claiming they spread diseases.

- May 1913: California passed the Alien Land Act, prohibiting Asians from owning land, houses, or buildings.

- April 27, 1916: The Labor Party circulated a resolution to boycott businesses employing or trading with Asians.

- August 3, 1916: Sacramento merchants resolved to boycott small Asian-owned shops.

- February 5, 1917: The United States banned immigration from most Asian countries, with exceptions for the Philippines and Japan, and introduced an English language test for immigrants.

- 1921: A new immigration law limited the number of immigrants from each country to 3% of the number of people from that country living in the U.S. as of the 1910 Census.

- May 15, 1924: The Oriental Exclusion Act banned all Asian immigration, even ending the so-called Gentlemen’s Agreement with Japan and preventing picture brides.

- July 1, 1927: Based on the 1920 Census, the U.S. decided not to allow immigrants from countries whose citizens were ineligible for U.S. citizenship.

- January 17, 1941: The U.S. government froze the assets of Japanese living in America and its territories.

- 1943: The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed.

- 1945: The War Brides Act allowed American soldiers to reunite with their foreign wives.

- 1947: Asian women married to American men were allowed to immigrate to the U.S.

- July 22, 1947: U.S. citizens’ spouses were allowed to immigrate regardless of race.

- June 27, 1952: The McCarran-Walter Act granted all races the right to become U.S. citizens.

Testimonies of Racial Discrimination

- Bang Sagyeom: In 1916, Bang Sagyeom and his wife opened a restaurant in Sentinela. They received threats to leave the area within a few days. Despite receiving support from the market manager, they faced harassment, including vandalism and customers refusing to pay. Eventually, they earned $5,000 in two years.

- Mary Paik Lee: In her autobiography “Quiet Odyssey,” Mary Paik Lee described arriving in San Francisco in 1906, where her family was spat on and insulted by whites at the pier.

- Dora Kim: Her family lived in Chinatown, San Francisco, because they were only accepted by the Chinese community. When crossing into the Italian neighborhood, they were often beaten by Italian children.

- Jang Inhwan: Children threw stones and broke windows of his laundry shop in San Francisco. Police did not respond to his complaints.

- An Yeongho: An Changho’s cousin was refused service in a restaurant and ridiculed. He threw a chair in frustration but was defended by the police for his reaction.

- Sonia Sunwoo: Despite her education, she was denied a teaching certificate in 1937 and faced harassment while camping in 1942.

- Joo Younghan: He faced discrimination in church and saw signs barring Asians from entering towns in the 1920s.

- Hwang Saseon: Arriving in San Francisco in 1913, he and his son faced employment discrimination despite their education.

- Choi Jeongik: His son was expelled from Emerson Elementary School for being Asian. Choi successfully fought the expulsion with the help of a school board official.

- Easurk Emsen Charr: After serving in WWI, his wife faced deportation due to anti-Asian laws, despite their American-born children.

- Jang Riuk: A restaurant refused to serve Asians, fearing it would drive away white customers.

- Jo Seonghak: Expelled from public school due to anti-Asian sentiment, he received private education from a supportive family.

- Ahn Changho: His visa application was denied in 1921, and he had to obtain a Chinese passport to re-enter the U.S. in 1924.

- Kang Yeongseung: Despite graduating from a prestigious law school, he could not find work and returned to manual labor.

- Seo Hakbin: Denied entry with his wife under the 1924 immigration law, they were forced to return to Korea.

- Han Sidae: Despite his wealth, white people threw stones at him for buying a car.

- Yeom Manseok: Beaten by whites in San Francisco who mistook him for Japanese during WWII, he later wore a badge identifying him as Korean.

Racial Discrimination in Southern California

Steward Incident: Mary Steward, who owned an orange farm in Upland, hired Koreans as workers. One night, white people threatened to kill them if they did not leave. Steward contacted the police, received permission for the Koreans to use guns in self-defense, and publicized the incident. Despite threats from white workers, she refused to fire the Koreans, stating they had the right to live and work like anyone else. Her resistance ensured the Koreans’ safety, and she introduced many Koreans to work opportunities in Southern California.

Leave a Reply