Dosan Ahn Chang-ho (1878–1938) arrived in America in 1902 with the intention of studying. However, seeing the Korean community in America without a focal point and drifting aimlessly, he felt sympathy and initiated an enlightenment movement within the Korean community.

He was a thinker and activist who emphasized the transformation and remodeling of his compatriots, who were bound by old customs and defeatist attitudes, and worked hard to inspire hope. Dosan believed that the development and cohesion of the Korean community in America were crucial powers to regain the nation. He believed that nurturing talents and economic revival could achieve his goals and boost national pride, making him a patriarch-like figure among the early Korean immigrants in America.

Dosan was born on November 12, 1878, as the third son of a poor scholar who farmed on Dorong Island, downstream of the Taedong River in Gangseo County, Pyeongan Province. After losing his father at the age of seven, he was raised by his grandfather. He attended a local village school where he befriended Phil Dae-eun, who was a few years older, and was exposed to new Western learning. Disturbed by the power struggles between China and Japan witnessed in Korea, he decided to learn about new Western ideas and moved to Seoul in 1894 to enter Gusehakdang (the predecessor of Kyungshin School). He graduated from the ordinary course after three years and became a teaching assistant. It was there that he and Phil Dae-eun converted to Christianity and attended Saemunan Church. At the age of 19, he joined the Independence Club, led by Seo Jae-pil, and along with Phil Dae-eun, formed the club’s branch in the western region. He made his first public speech at a mass meeting in Pyeongchang and received enthusiastic applause from the audience. He then spent about three years traveling through Gyeonggi, Hwanghae, and Pyeongan provinces, giving speeches to awaken national consciousness.

At 21, he founded Jomjin School in Anhwa-ri, Dongjin-myeon, Gangseo County, to introduce common people to new Western learning. At 24, he married Lee Hye-ryeon, a graduate of Jungshin Girls’ High School, and decided to study in the United States to further his education. While traveling to the United States, he marveled at an island that appeared suddenly in the vast, blue Pacific Ocean and named himself ‘Dosan,’ which means ‘island mountain.’

Upon his arrival in San Francisco

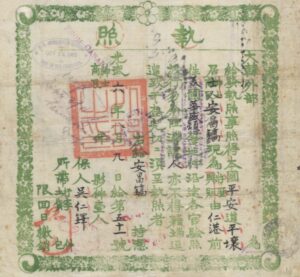

Dosan landed at Vancouver, Canada, in September 1902, passed through Seattle, and arrived in San Francisco on October 14 at the age of 24. His passport was number 51, making it one of the oldest Korean passports issued in America. Shortly after his arrival, he witnessed two Koreans fighting over a topknot in the street, which shocked him. Realizing the dire state of Koreans in America, who fought over minor rights and lived in unclean conditions, he felt compelled to act. Despite his original intent to study, he put education aside to focus on enlightening his fellow Koreans.

He began with a cleaning campaign, visiting Korean homes to clean windows, hang curtains, and plant flowers. This movement toward cleanliness changed the local Koreans’ habits, such as shaving more often and dressing neatly, which impressed their landlords.

Dosan organized the Sanghang Friendship Association to unify Korean labor and ensure fair wages through negotiations with American employers. He later established the Public Association and published the Public Shinbo newspaper, which extended its reach to Koreans in San Francisco, other cities, Hawaii, and Mexico, culminating in the formation of the Korean National Association.

On September 23, 1903, he founded the first Korean community organization in America, marking the start of the national movement. He continued to lead and expand the association, becoming its first chairman and guiding the efforts of Koreans abroad in the fight for their country’s independence.

In 1907, during a trip back to Korea, Dosan spoke at Taeguk Academy in Japan, inspiring many students to join the independence movement. He organized the Sinminhoe (New People’s Association), which focused on education and industry, and supported it through businesses like the publishing company Taeguk Bookstore in Pyongyang, Seoul, and Daegu. He also founded Cheongnyon Hakwoo, a precursor to the Heungsa Dan, Korea’s first youth organization, in 1909.

In February 1909, the Korean community organization in San Francisco was integrated into the Korean National Association. Dosan was appointed as the first president of this association, guiding the national movement of Koreans abroad. That same year, following a similar national organization effort in Korea, when Ahn Jung-geun assassinated Ito Hirobumi, Dosan was implicated and detained by the Yongsan Military Police for two months. In 1910, the Japanese governor-general, Ito Hirobumi, proposed forming an “Ahn Chang-ho Cabinet,” which Dosan rejected. Following the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910, Dosan went into exile in 1911.

Dosan believed that Korea’s independence could only be achieved through the collective strength of the nation. Leaving behind the famous “National Anthem” for the mountains and people of Korea, he promised to reclaim the lost glory of his homeland and left Korea, which was under Japanese rule. During his stay in Vladivostok, also known as Haesamwi due to its abundance of sea cucumbers, he planned the training of independence fighters and scouted locations in Manchuria for building a new village. In Qingdao, China, he gathered exiles and held the Qingdao meeting. However, the group split into those advocating immediate armed resistance against Japan and those who wanted to focus on fostering industry and education as preparations. Dosan’s nationality was also an issue as he crossed borders, with British authorities, allies of Japan, labeling him a “Japanese subject.” Dosan insisted that he could not be a Japanese subject as he was a political exile, and he was eventually recognized as Korean. Later, he traveled as a stateless person, indicated by his “without passport” status from the U.S.

In 1912, Dosan became the inaugural chairman of the Central General Assembly of the Korean National Association organized in San Francisco. From 1913, the association was recognized by the U.S. State Department and the government of California as a self-governing body, significantly enhancing the autonomy and rights of the Korean community. On May 13, 1913, Dosan organized the Hung Sa Dan (Young Korean Academy) in the house of Gang Yeong-so in San Francisco, gathering 25 representatives, including eight youths representing the eight provinces of Korea, aiming to eliminate regionalism and factionalism and train an elite group to lead the independence movement. The movement focused on rectitude, healthy personalities, unity training, and national enterprise as its objectives.

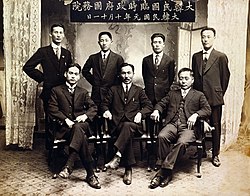

In 1917, Dosan traveled across Mexico, visiting Koreans suffering from poor immigration conditions, and returned the following year. In February 1919, a national assembly was held in San Francisco, and Syngman Rhee, Min Chan-ho, and Jung Han-kyung were elected to represent the Korean cause at the Paris Peace Conference. The March 1st Movement erupted soon after, and in April, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was established in Shanghai, with Dosan appointed as the Minister of the Interior, marking his return to Shanghai after seven years and seven months in the U.S.

In Shanghai, Dosan arrived on May 25, 1919, with $25,000 raised by the Korean National Association in America, which greatly aided the provisional government. He took office as the acting Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior on June 28, 1919, in Shanghai, where he implemented a communication system to link overseas organizations with domestic efforts, enhancing the independence movement. He also played a key role in organizing the Provisional Assembly and establishing the Korea Independence Party, advocating for overseas Koreans to contribute financially to the military funds of the provisional government. He published the newspaper “Independence” to guide the direction of the independence movement.

On January 15, 1920, he began work with the Hung Sa Dan and established the headquarters of the Korean Liberation Army in southern Manchuria. On June 18, 1920, he prepared for the visit of a U.S. congressional delegation touring the Far East, appealing for support for Korean independence. In 1921, he broke with Syngman Rhee and, along with Kim Kyu-sik, resigned from the provisional government. Although he was repeatedly recommended for the position of prime minister, he declined.

On January 3, 1923, at the National Representatives Meeting held in Shanghai, Dosan became the acting chairman as the representative of the Korean National Association in America. However, due to severe disagreements between reformist and revolutionary factions at the meeting, Dosan went to Northern Manchuria to promote the establishment of Isangchon, a base for the independence movement, and spearheaded a campaign for its construction among the general populace.

In 1924, he established Dongmyeong Academy in Nanjing to prepare students for studying abroad and to assist in developing their capabilities. On December 16, 1924, Dosan arrived in San Francisco and toured various locations to strengthen the organizations of the Korean National Association and Hung Sa Dan. He led efforts to raise funds for the construction of Isangchon and for supporting the provisional government’s maintenance costs in America. Under Dosan’s leadership, the Korean National Association contributed a head tax to support the provisional government. Returning to Shanghai, he was appointed as the third State Minister of the Provisional Government on February 20, 1926, but he resigned to set strategic directions for the independence movement in six areas: military, diplomacy, finance, culture, industry, and unity, and discussed the formation of the Greater Independence Party. During this time, he and about 200 of his comrades were imprisoned by Chinese police. Released after 20 days, Dosan continued to work fervently on the construction of Isangchon, but continued assassinations of key figures like Kim Jwa-jin and setbacks like the Manchurian Incident eventually forced him to abandon the project. He led the efforts for a unified provisional government, the National Representatives Meeting, and the Sole Party Movement in China.

In March 1928, Dosan organized the Korea Independence Party, and in 1929, he visited the Korean community in the Philippines and toured Pine Village to look for potential construction sites for Isangchon.

In 1930, he organized the ‘Donginhoe Research’ to gather the strength of Koreans in Shanghai to enhance their capabilities for living. In January 1931, he presided over the 17th convention of Hung Sa Dan as the chairman and published the Hung Sa Dan newsletter to spread its ideology. He also supervised the publication of the magazine ‘Donggwang’ in Korea. When the Patriotic Women’s Association set up plans to raise funds for military contributions in line with the purpose of Hung Sa Dan, Dosan renamed Donginhoe Research to Gongpyeongsa and became its chairman, promoting joint movements for consumption, credit, and production to increase living capabilities. That same year, after the Manboksan Incident led to conflicts between Koreans and Chinese worsening sentiments, various groups including the Veterans’ Association, Korean Community Group, Student Association, Young Women’s Alliance, Patriotic Women’s Association, and Youth Alliance united to form the ‘Shanghai Korean Organizations Union.’ Dosan participated as a representative of Hung Sa Dan and advocated for strengthening the anti-Japanese struggle jointly with China. In October 1931, he also served as an adjudicator for the Korean Community Group alongside Yi Si-yeong.

During the peak of his activities, on April 29, 1932, after the Hongkou Park incident by Yun Bong-gil, Japanese authorities began a crackdown on independence activists. Despite being aware of this, Dosan went to the house of Lee Yoo-phil, the leader of the Korean residents in Shanghai, to deliver a promised donation of 2 yuan to Lee’s young son. Despite his comrades’ strong objections, Dosan believed that “we should not disappoint or betray the trust of children.”

However, Dosan, who then held Chinese nationality, was arrested without a warrant by French police and handed over to the Japanese consulate. He was extradited to Korea, where the Seoul District Court sentenced him to four years in prison, and he served time in Seodaemun and Daejeon prisons.

Released from Daejeon prison in 1935 due to worsening stomach disease, Dosan continued to give enlightenment lectures under Japanese surveillance. He then retreated to Daebosan in Pyeongannam-do to plan the construction of Isangchon, but in 1937, he was arrested again with 191 others in the Suyangdongwoo Association incident. While imprisoned, he was released on bail in December of the same year due to liver tuberculosis combined with tuberculous peritonitis.

On March 10, 1938, at 12:06 PM, while hospitalized at Seoul National University Hospital, Dosan passed away at the age of 60. The Japanese authorities stated, “As Ahn Chang-ho was a defendant in the Dongwoo Association case, a formal funeral is not permitted, and his family is not allowed to wear mourning attire. Of course, no one can follow the hearse.” Outraged, Oh Ki-young protested, “Is it chivalrous to not even allow the chief mourner to wear mourning attire?” highlighting the lack of generosity in Japanese politics. Consequently, only the chief mourner was allowed to wear mourning attire, and only Jo Man-sik, who had received special permission, followed behind. It was an unusual funeral with more plainclothes policemen standing at a distance than mourners. Guards lined the route to the grave, prohibiting all vehicular traffic. Concerned about public unrest, the Governor-General’s office controlled all media coverage and arranged for the burial in the Manguri public cemetery instead of a family grave, limiting attendance to about 20 family members and Christian associates. Relatives planted a rose of Sharon at the grave, but Japanese police intervened, instructing them to cut it down and plant cherry blossoms instead.

During his lifetime, Dosan spent 34 years in Korea, 13 years in Shanghai, and 13 years in America.

In 1962, the South Korean government posthumously awarded Dosan the Republic of Korea Medal, the highest honor of the Order of Merit for National Foundation.

Leave a Reply