The official immigration to the United States began with labor immigration for cultivating sugarcane fields in Hawaii. At that time, the Joseon Dynasty was plagued by political turmoil, economic oppression, and exploitation. Japanese individuals were buying up farmlands, leading the local peasants to lose their lands and suffer under the corruption of greedy officials. Moreover, a severe drought in the Hamgyeong-do region in 1901 caused a food crisis, forcing many to seek food and work in far-off places like Siberia, Manchuria, or major cities such as Seoul, Incheon, and Wonsan. To make matters worse, in the summer of 1902, outbreaks of cholera and typhoid fever caused the deaths of 300 to 400 people daily.

In response, Emperor Gojong, anticipating another poor harvest in the coming fall of 1902, issued an order on July 26 to ban rice exports and suspend non-urgent civil works. Additionally, he issued a decree to release prisoners convicted of serious crimes and ordered health officials to concentrate their efforts on containing the epidemic.

Meanwhile, Hawaii, which had started intensive sugarcane agriculture since the 1830s, required cheap foreign labor, leading to formal labor immigration agreements with Asian countries starting in 1864. An immigration bureau was officially established to manage foreign workers, and by 1882, nearly 50% of these workers were Chinese. In an attempt to counterbalance this, Japanese workers began to be accepted, and by 1902, they constituted 73% of the workforce. With the enactment of the Organic Act in 1900, Hawaii became a territory of the United States, changing its administrative system and applying U.S. law to Hawaiian workers, marking a significant change for them.

This also paved the way for labor immigrants to move to the U.S. mainland. Coincidentally, California began to extensively develop fertile farmland, and many workers, longing for the mainland, started to migrate there. This led to a labor shortage in Hawaii, prompting Japanese workers to strike 34 times between 1900 and 1905. Consequently, feeling the need to quash and counter these strikes, the Hawaiian Sugarcane Planters’ Association took an interest in Korean laborers. They requested the U.S. Consul in Korea, Allen, to propose overseas immigration to Emperor Gojong.

Horace Allen, a medical missionary sent by the Presbyterian Church of the USA, arrived in Seoul on September 22, 1884.

Horace Newton Allen (April 23, 1858 – December 11, 1932):

an American Presbyterian medical missionary, educator, and diplomat who served in Korea for nearly fifty years. He is best known for his work as the first foreign medical doctor in Korea, his role in founding the Presbyterian Church in Korea, and his service as the United States Minister to Korea from 1897 to 1905.

He became the royal physician after treating Min Young-ik, who was injured during the Gapsin Coup, and with government support, he established Gwanghyewon, the precursor to Severance Hospital, and taught medicine. He was favored by Emperor Gojong and subsequently became the U.S. Consul to Korea.

Actively advocating for the opening of America’s doors to Koreans, he returned to the U.S. for a vacation at the end of 1901. On his return journey, he met Irwin, a director of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association (HSPA), in San Francisco and learned about the labor shortage in Hawaii. It was then that he planned the promotion of Korean immigration to America. At that time, the population of Seoul was about 200,000.

Consul Allen, who had a close relationship with Emperor Gojong, returned to Seoul and, in an audience with Emperor Gojong, argued that “sending people to Hawaii to introduce new farming methods and new culture would be a wise policy, especially since the people are not only aspiring to progress but are also suffering due to poor harvests.”

Believing that it was better for Korea to maintain close ties with the United States to preserve its independence from surrounding powers, Emperor Gojong approved the immigration to America. With the emperor’s consent, Allen sent a report to the U.S. stating:

“It seems Emperor Gojong has a sense of pride that while Chinese entry was being rejected, the entry of Koreans was allowed.”

On May 9, 1902, posters began to appear across Korea under the name of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association, recruiting people for immigration to the United States.

The employment-based immigration of workers has begun to be promoted. A person named Deshler, who established the “East-West Development Company,” was in charge of the practical work. Deshler was a friend who had supported Allen’s political career. Allen arranged the labor as a way to repay his debt to him. In return, he received $55 for every worker recruited by the farm. Having a Japanese wife and a home in Japan, he planned to start a transportation business using his boat. Transporting workers to the US via Japan first was simply a matter of time before it would become a lucrative endeavor.

Allen, who was proactive in immigration, even wrote to the Governor of Hawaii saying, “Koreans are a patient, diligent, and docile race, and due to their long history of obedience, they are easy to manage.”

At the time, there was criticism from the farms that the Chinese ate a lot, resulting in higher food costs. Perhaps because of this, Allen wrote that “Koreans are more gentle than the Chinese, and although their staple food is rice, they consume more meat than the Chinese.” He also requested that funds be lent in advance since Korean workers were poor and the government had no intention of providing travel expenses. This request was accepted, greatly widening the immigration opportunities for even those who couldn’t afford the ship fare.

This money, called an advance, was $150 and covered the ship fare and food expenses for immigration. Farm owners preferred hiring Asians over Europeans because it was significantly cheaper—approximately $70 per Asian compared to $150 per European. In response to these circumstances, King Gojong appointed Min Young-hwan, who was knowledgeable about overseas affairs, as the head of immigration affairs. On August 20, 1902, he launched the ‘Su-Min-Won,’ an agency equipped with the functions of an overseas development company, within the Royal Household Ministry, and heavily advertised immigration recruitment through major newspapers and flyers in large cities like Seoul, Busan, Incheon, and Wonsan.

The advertisements stated, “Anyone going to Hawaii will receive government assistance. Hawaii has a favorable climate, schools do not charge tuition fees, English is taught for free, the monthly salary is 15 won (about $15 or 67 won), work hours are 10 hours a day with Sundays off. Housing and drinking water are provided, and if you fall ill, the employer will cover the medical costs.”

However, the people were indifferent to leaving their ancestral lands, which they considered a grave sin, as well as leaving their families and hometowns.

Therefore, in Chemulpo (now Incheon), where a fierce competition for trade rights among the great powers was underway just 10 years after the port was opened, Pastor G.H. Jones of Yongdong Church (currently Naeri Methodist Church) actively encouraged his parishioners to immigrate. Thanks to him, half of the first 121 immigration supporters were from Pastor Jones’ church. Consequently, many of the early Korean settlers in the United States were church members, leading to a church-centered Korean-American community in the future.

1901 Naeri Methodist Church

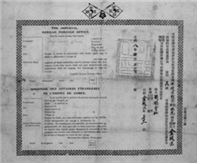

The first group of immigrants, totaling 121 individuals, including 50 male and female church members, 20 laborers from Jemulpo Harbor, and 51 people from various occupations from all over the country, boarded the first immigration ship carrying passports issued in the name of Min Yeong-hwan.

When the passport system was first introduced in our country, the term used was jipjo, which meant an identification document. The word jipjo generally referred to any official document issued by a government office and did not initially imply a passport. However, as foreign interactions increased following the opening of the ports, the term ‘집조’ began to include the meaning of a passport.

Among these people were members of the Yongdong Church, students aiming to study, rural scholars, soldiers, rural servants, porters working odd jobs, and even some ruffians. About 65% of them were illiterate, and almost none could understand English. Their primary motivation for immigrating was to escape the political and social turmoil caused by Japanese aggression and to overcome economic hardships. The first immigration ship left Jemulpo on December 22, 1902, and reached Kobe, Japan, where the immigrants underwent medical examinations to determine their eligibility to enter the United States.

The ship Gaelic carried the first Korean immigrants to Hawaii. 20 individuals were rejected, and only 101 arrived at Honolulu Harbor on January 13, 1903. This group included 56 men, 22 women, and 23 children. Shockingly, 8 more were denied entry due to eye problems and had to return. Thus, 93 Koreans entered Hawaii on the Gaelic. Between 1903 and 1905, 6,048 men, 637 women, and 541 children immigrated in 15 voyages, totaling 7,226 people.

Despite enduring seasickness and a long month at sea, 479 were sent back to their homeland due to health issues. One can only imagine the disappointment of those who had to make the long journey back. Previously, a few ginseng merchants and students were in San Francisco, but the official immigrants who were sent through the Immigration Agency, called Suminwon, of the Korean Empire, are considered the pioneers of immigration. Dreaming of eventually returning to their homeland enriched, they harbored hopes as they settled in a strange land, making them the true pioneers of immigration to the Americas.

Leave a Reply