In the early 1900s, California was filled with the fervor of pioneering. Wastelands transformed into fertile farmlands, and a transportation network that connected major cities across California was completed, linking the West Coast to the East.

The sight of railroad construction alone was enough to excite people about the future. Such large-scale projects were beyond the local workforce in California, necessitating the influx of labor from other regions. Asians, known for their diligence and lower wage demands compared to Americans, naturally increased in number in California. This pioneering news was also enticing to Koreans in Hawaii, especially since wages in California were significantly higher compared to those in Hawaiian plantations, which were about one-third to half less than similar labor in the mainland. The people in Hawaii, desiring better opportunities, viewed the mainland as a promising new frontier. After enduring years of hardship, the Koreans in Hawaii saw migration to the mainland as an even more desperate aspiration.

Those who had initially come to Hawaii for education also yearned to move to the mainland, where they perceived better opportunities for work, schooling, and living conditions compared to Hawaii.

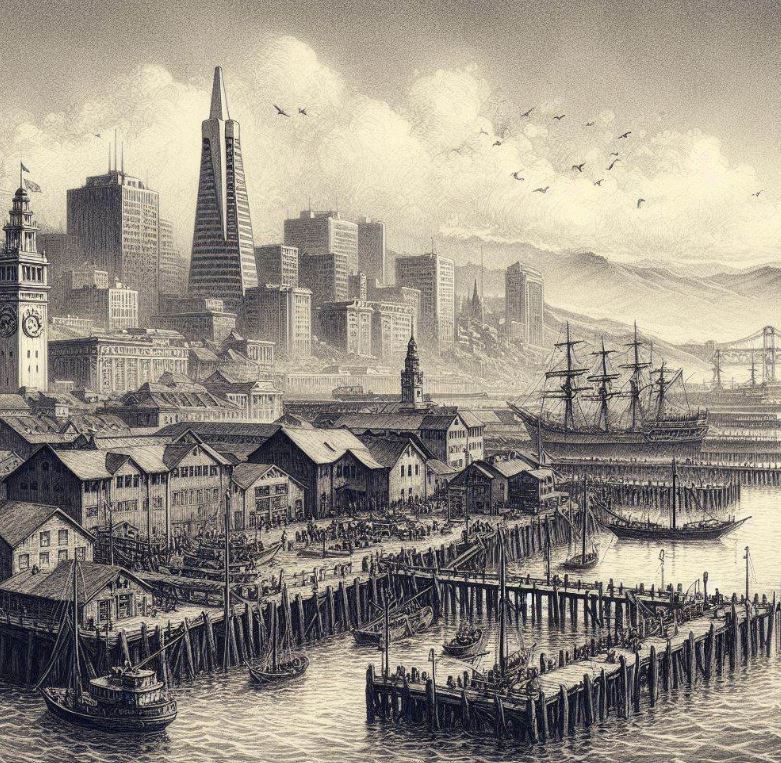

Encouraged by Yun Chi-ho, Yun Eung-ho set his sights on San Francisco, and Yang Ju-eun also decided to move to the mainland for his studies. Between 1904 and 1907, over a thousand people migrated from Hawaii to San Francisco. According to Professor Moon Hyeong-jun’s “The Korean Immigrants in America,” between 1903 and 1913, around 400 to 500 Koreans moved from Hawaii to the mainland, with about half of them hoping to attend school. The climate was another reason Koreans wanted to move; having lived in the distinctly seasonal Korean peninsula, the intense daily heat was challenging, and California’s pleasant all-year climate and abundant job opportunities were highly attractive. San Francisco, a gateway for Asians entering the U.S. mainland and a hub for trade with East Asia, became an appealing city for Asians due to its active cultural exchange.

In 1903, the Union Pacific and the Pacific Railroad companies began laying tracks from Seattle, Washington, to St. Paul, Minnesota, recruiting an astounding 20,000 workers. Moon Hong-seok, having obtained the position of recruitment agent, opened an office in his Hanseong Inn in Honolulu.

From March 1905, the recruitment began in earnest, marking the start of many Koreans’ migration to the U.S. mainland. The journey from Honolulu to San Francisco by ship took six days and cost about 28 dollars. Subsequently, recruitment notices for railway construction and agricultural development in California became frequent in Hawaii.

On March 12, 1906, a public notice indicated that although Koreans coming from Hawaii to the mainland were very poor and often had no travel expenses, the Public Association arranged for their farm jobs, accommodation, and railway fares.

In March 1907, the U.S. government, through the Gentlemen’s Agreement with Japan, imposed measures to prevent Hawaiian immigrants from advancing to the mainland.

By 1912, the situation for Koreans in Hawaii seeking to move to the U.S. was such that they had to prove they had been residents for at least seven years to qualify for migration, and even then, they needed sufficient funds.

Initially, those who came to the mainland were helped by Dr. Drew, a missionary in Korea, ensuring they passed medical exams. Financial guarantees were provided by the Public Association, and these migrants worked in Californian agriculture or fruit farms, moved to Utah or Wyoming as coal miners, or went to Arizona as railway workers, and some even embarked on deep-sea fishing trips to Alaska.

Statistics on Korean Laborers Moving to the Mainland

According to the 1910 U.S. Census, there were 4,533 Koreans in Hawaii and 462 Koreans on the U.S. mainland. However, records from the Immigration Office state that more than 1,000 Koreans moved from Hawaii to the mainland from 1905 to 1910. During that period, 300 returned to Korea, and 200 came directly from Korea to the mainland, which suggests that there should be at least 900 people. The reason for the recorded number being only 462 may be due to some individuals not participating in the census and errors in properly documenting nationalities. It’s also reported that the inability to distinguish between Koreans and Japanese may have led to Koreans being misclassified as Japanese, using the derogatory term “Jap.”

According to the Hawaiian Immigration Office, between 1905 and 1907, the number of Koreans who moved from Hawaii to California was 399 in 1905, 456 in 1906, and 148 in 1907, totaling 1,003 people. In March 1907, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 589, which prevented Japanese and Korean laborers in Hawaii from moving to the U.S. mainland, effectively stopping further migration.

Although the numbers vary across sources, consolidated records indicate that from 1905 to 1910, a total of 1,015 people moved from Hawaii to the mainland, including 941 men, 45 women, and 29 children. From 1903 to 1910, only 103 Koreans came directly from Korea to California, significantly fewer compared to those who migrated from Hawaii. During this period, from 1903 to 1904, a total of 50 people moved, followed by 3 in 1911, 7 in 1912, 18 in 1914, and 15 in 1915.

Early Korean immigrants wait for ships from their homeland at the San Francisco docks.

Leave a Reply